September 2021, Vol. 248, No. 9

Features

Western Basins Staying Alive in New Mexico, Colorado

By Richard Nemec, Contributing Editor

New Mexico covets its long-held tourist designation as the “land of enchantment” from its more pastural days, but more than tourism, oil and natural gas dominate its economy today.

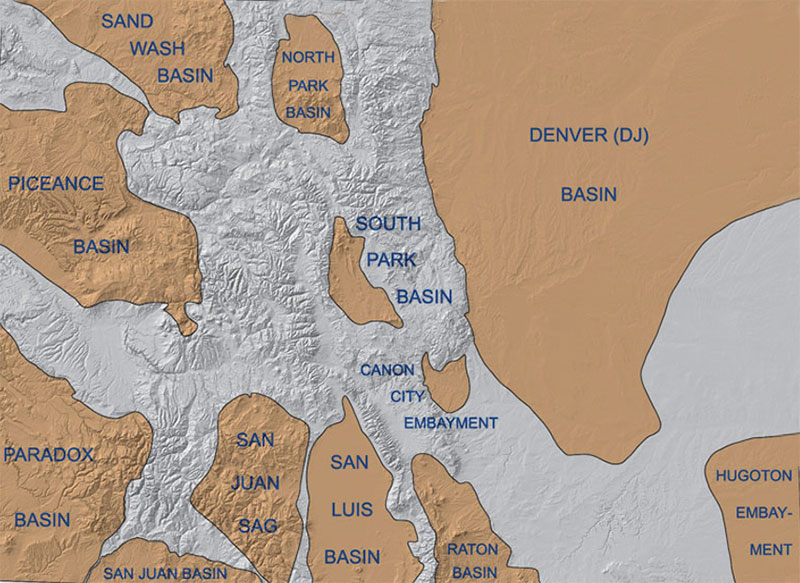

With its portion of the rich Permian Basin booming, the state is about to overtake North Dakota (Bakken Shale) as the nation’s second largest oil producing state, flowing more than 1.1 MMbpd. Somewhat forgotten to the north and west is the San Juan Basin with a 100-year history for oil and mostly natural gas production that historically helped support the far West population boom post-World War II.

Straddling the border with Colorado in parts, the San Juan Basin is primarily a gas-producing region, but since the advent of hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and horizontal drilling earlier in the 21st Century, it has also been known for crude oil.

Originally, the Mesaverde formation was the biggest play in the San Juan. The Texas Mexico (TexMex) pipeline originally took oil from the Aneth Field in Utah to Jal, N.M. Western Refining Inc. bought the line with the intent of transporting oil in the reverse direction from Jal to its two refineries in San Juan County.

There was insufficient oil available in the San Juan Basin to supply both refineries, so Western filled the pipeline with West Texas supplies from Jal to San Juan and then discovered that there was too much sulfur content for the oil to be used efficiently by these plants.

Eventually, the TexMex line was reversed again to flow oil from San Juan to Jal, the two refineries were closed in the San Juan, and a part of Marathon Petroleum Corp. now owns and operates the pipeline. Most San Juan oil moves to market on this pipeline, and the volumes that don’t use truck or rail transportation.

“My geologist friends tell me the San Juan is a plunging syncline,” said John Alexander, vice president with Dugan Production Corp., a small independent headquartered in Farmington, NM. (Unlike anticlines, “synclines” only form structural traps for petroleum when the depressed strata occur above the water table in dry rocks and oil gathers in the bottom by gravity flow.)

“There are structural traps with no folding or faulting, nothing like that. What we are getting here gas wise are the remains of a bunch of Cretaceous Age sea critters that died and fell out,” he added.

While unfamiliar with surrounding basins, Alexander knows his way around the San Juan and sees it as a steady but not spectacular play. “We kind of live and die by natural gas prices as a very mature basin that is very well defined,” said Alexander, who serves on the board of the New Mexico Oil & Gas Association. “We’ve got thousands of wells up here. All of the known geologically successful zones have been developed.”

Outside of the realm of technological advances not foreseen now, Alexander thinks there are slim chances that the San Juan will accelerate what has been a declining natural gas play for years. He also said you cannot discount the industry’s innovation and ability to create new technological approaches; he has lived through some of those.

“Just about every square acre that we have [at Dugan] is held in production by somebody,” he said.

Underscoring this assessment as applied to another basin, an ExxonMobil spokesperson Julie King told P&GJ that Exxon’s subsidiary XTO Energy earlier this year sold its operated and non-operated assets in the Piceance Basin to privately held, Denver-based Caerus Operating LLC.

“The sale aligns with ExxonMobil’s strategy to focus on “advantaged assets with the lowest cost of supply,” including developments in Guyana, Brazil and the U.S. Permian Basin,” King noted.

Dugan Production uses Enterprise Products Partners LP, along with Harvest Midstream, the old Williams Cos. System, as its takeaway outlets. An unprecedented February 2021 freeze hurt them on Harvest, but not as much on the Enterprise system this past winter. “Demand ruptures like we experienced in February caught everyone up short,” Alexander said.

Except for a few minor exceptions, Alexander said his operations have not been constrained by pipeline capacity limits. “When some of the new Mancos Shale wells come online, they have pretty high levels of recovery and it can cause some displacement of gas moving under the same gathering system,” he said.

Enterprise operates an extensive natural gas gathering system serving producers in the San Juan Basin, delivering production to the Chaco and San Juan gas processing facilities. Natural gas ultimately gets delivered into El Paso Natural Gas’ pipelines. It delivers natural gas liquids (NGL) to MidAmerica Energy’s NGL pipeline and the Wingate fractionation plant in Gallup, N.M.

Colorado basins are really different from one another, according to Dan Haley, CEO of the Colorado Oil & Gas Association (COGA). The Denver-Julesburg (DJ) Basin is primarily an oil and natural gas liquids play, with some associated gas. Along the West Slope, the Piceance Basin is the second largest natural gas play in the country behind the Marcellus Shale in Appalachia. The San Juan Basin is characterized broadly as a valuable coalbed methane (CBM) asset that private companies and the Southern Utes Native American Tribe have consistently developed for decades.

“The biggest challenges facing the oil and gas industry are really threefold,” Haley said. “The business model has changed as companies are merging or growing through acquisitions, with a focus on stable revenues and more predictable profits, rather than previous business models more focused on growth. Second, Colorado’s regulatory framework is incredibly robust, requiring local companies to make significant investments in their regulatory teams and operational practices. Third, global commodity prices are fluid, and the actions of Russia and OPEC are often unpredictable, but that’s been a consistent challenge for decades.”

Affecting two of the basins, Colorado’s state and local energy regulatory rules and processes are undergoing a complete transformation that is heightening the concerns from industry operators. For operators the rating agency Moody’s Investors Service has concluded that the uncertainty accompanying the transition is a “material” issue that has to be considered in assessing risk profiles.

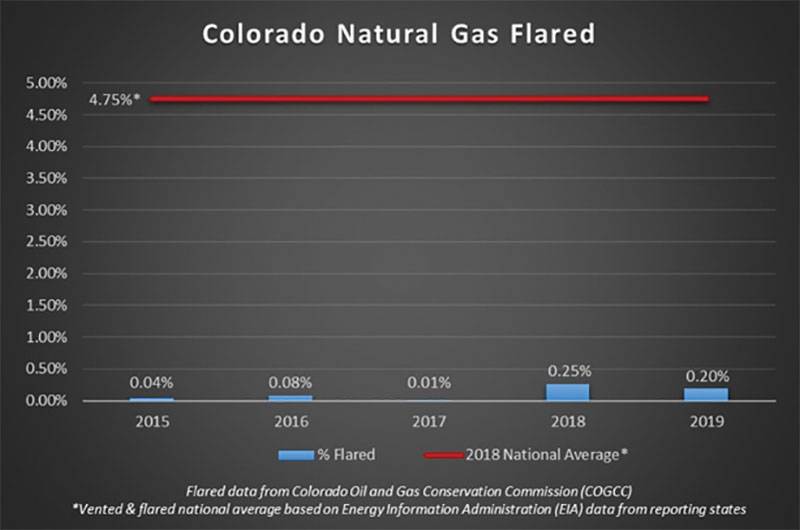

Nevertheless, “prospects for local production are good,” said COGA’s Haley, noting that the regulatory overhaul is nearing completion. “We should begin seeing new permits awarded soon,” he noted in late July. “D-J remains valuable, and the top shelf operators that are here will be able to successfully navigate the rigorous requirements and produce some of the cleanest energy molecules on the planet.”

The D-J Basin has attracted exploration and production (E&P) activity for more than 40 years since the Wattenberg Field, located primarily in Southwest Weld County, was discovered in 1970, and was one of the 15 largest U.S. proved gas fields in 2009, according to the U.S Energy Information Administration (EIA). The majority of production from the Wattenberg initially came from vertical drilling in the Niobrara/Codell formations, and the Muddy J Sandstone, a tight sands play that lies several hundred feet below the Codell.

Enter the Majors

In 2021, the D-J has attracted some good-sized players, one of which is a recent creation of a merger and major acquisition. Occidental Petroleum Corp., Chevron Corp., PDC Energy Inc., and the newly formed Civitas Resources Inc. are the four largest oil and gas producers in the D-J. Civitas was formed by a $2.6 billion merger of Bonanza Creek Energy and Extraction Oil & Gas, followed by a $4.5 billion purchase of Crestone Peak Resources a month later last spring.

“They are all shifting toward a business model based on stable and predictable production, and the associated revenues, rather than a model primarily focused on production growth,” Haley said.

EOG Resources kicked off the trend toward horizontal drilling in the Niobrara D-J. Much of the horizontal drilling for the Niobrara and the Codell that has occurred since then has been in the Wattenberg, and to a lesser extent in and around the Silo Field in Southeast Wyoming. These have been the most heavily targeted areas because a lot of acreage was held by E&Ps and existing takeaway infrastructure was already in place.

One of the D-J’s major midstream companies, Kinder Morgan (KM), is part of a four-company collaborative seeking to lower methane emissions in the natural gas production-to-end-use value chain in Colorado.

In March this year, a producer, infrastructure operator, and local municipal utility entered into a first-of-its-kind Responsibly Sourced Gas (RSG) agreement with Denver-based Project Canary to provide continuous emissions monitoring data and technologies across the energy sector. The wellhead-to-burner-tip RSG pilot covers production, transportation and marketing of RSG for consumer and community use locally in Colorado.

In the pilot project, city-owned Colorado Springs Utilities will purchase certified RSG produced by locally based Baywater Exploration & Production. The certified RSG will be gathered and processed by Rimrock Energy Partners, a provider of midstream services in the D-J Basin, before being delivered to KM’s Colorado Interstate Gas Company, which will transport the RSG to the utility.

As a member of the ONE Future Coalition, Kinder Morgan is part of a group of companies working to voluntarily reduce methane emissions across the natural gas value chain to 1% or less by 2025. Project Canary will provide technologies, data monitoring to measure methane emissions, and independent RSG certification.

Some industry analysts question the lack of a widely accepted standard for the RSG certification. Project Canary’s methodology is not universal. Its approach deploys a technological system that continuously monitors the operations and emissions of methane and volatile organic compounds at oil and gas sites, including wells, pipeline, and storage systems.

Project Canary uses that data, along with a data validation system to track emissions, while offering an opportunity for the oil and gas companies to measure and make progress on ESG (environmental, social, governance) issues. ONE Future’s members contend that they measure their emissions and track their progress over time according to uniform, Environmental Protection Agency-approved reporting protocols.

In early 2021, Moody’s analysts assessed two very different sized operators in the D-J Basin – PDC Energy and Great Western Petroleum LLC – both of which have strong ties to the Colorado basin. Moody’s liked PDC’s size (190,000 boe/d) although the rating agency sees the company as “constrained” by its primary production being tied to mostly one basin, D-J.

In contrast, PDC has a “large drilling inventory with considerable flexibility,” Moody’s said. Although small, Great Western benefits from low-cost acreage in the D-J, Moody’s analysts concluded in March.

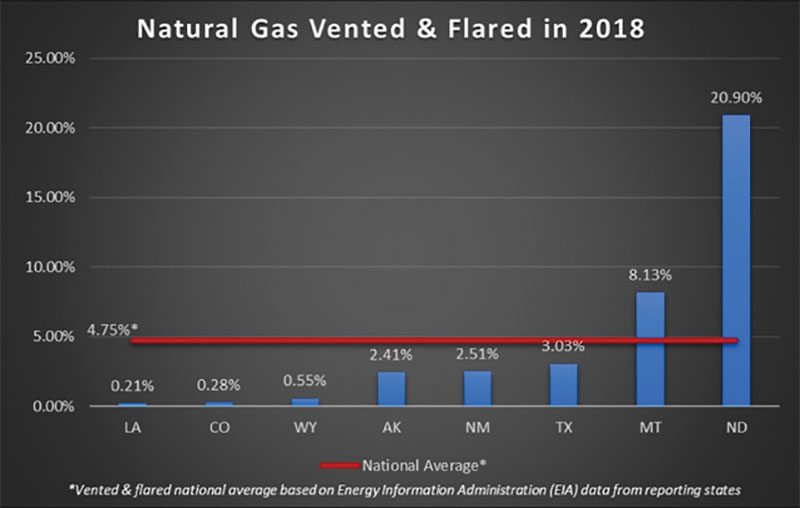

In the Colorado basins, PDC in the first quarter this year achieved no flaring from its operations, and CFO Scott Meyers noted that some of the E&P’s best economics were seen in its operations in D-J’s Wattenberg field. Over the same period, Great Western cut by nearly 50% its cost of drilling in the D-J by using twin drilling rigs on each pad.

“Each well takes about eight days to drill; depending on the site and number of wells, that could mean our crews are spending four months drilling onsite versus eight months,” said CEO Rich Frommer. “This program is unlike any other throughout Colorado; it drastically reduces the impact to nearby communities, increases operational efficiencies, and saves everyone money – further cementing Great Western’s position as an industry-leading innovator in natural gas and oil.”

Along with the environmental existential drivers, all three western basins are tracking the growing U.S. liquefied natural gas (LNG) export market as an important stimulus for future demand increases. “If we’re producing some of the cleanest energy in the world, then we need the opportunity to get that energy to the world,” said Haley in response to questions about the Sempra Energia Costa Azul (ECA) LNG export project along the North Baja California Pacific Coast in Mexico.

“COGA members support export infrastructure to achieve that goal, and we hope elected officials will understand that and support projects that strengthen our environmental security, both locally and globally. If we lean into and rely on producers that are developing safe, clean, and responsible sourced energy, everyone wins.”

San Juan’s Alexander has a different take, somewhat ambivalent, but very much interested in outlets like the ECA terminal now under construction with a 2024 in-service date.

Follow the Money

“A number of people think [the Baja LNG project] will be positive, but there are producers who are not impressed,” he said. “The question is what sort of capacities a terminal like that can provide. Most pipelines out of here move gas west into California. Capacity is not an issue out of the San Juan.

“LNG is interesting because it could have the capacities we need to get some of our supplies on ships for supplying other countries; a lot of it also depends on how quickly the world comes out of the impact from the Covid-19 pandemic,” Alexander said.

Alexander said he is just ready to “follow the money,” which for the future is tied to LNG exports. “We’d be more than willing to keep the gas in foreign countries if it helps to keep the price of gas up,” he said.

At a gas industry conference in July in Boston, a representative from PointLogic, a Neilson Company subsidiary and marketing analytics consultant, predicted that deliveries to U.S. LNG facilities should average more than 11 Bcf/d in the last half of 2021, dropping to a peak around 9.5 Bcf/d during parts of 2022, and rising to more than 13 Bcf/d by the end of 2023.

The global consultant envisions minimal U.S. cargo rejections while U.S. demand for electricity generation is trending downward after peaking at 31.7 Bcf/d in 2020. Renewables are likely to continue to shave the total gas volumes going for power generation.

As Dugan Petroleum’s Alexander and COGA’s Haley articulated, their respective U.S. western basins are not aloof from global commodity and socio-economic issues. Earlier this century, the San Juan infrastructure was influenced by the U.S. shale boom and global commodity pricing.

Alexander recalled that Enterprise’s Chaco processing plant that had been created by the old MidAmerican Energy Co. pipeline system converting a NGL line to carry crude oil. And when the shale boom was full blown, MidAmerican looped all of its gas pipelines serving the San Juan. Enterprise later purchased MidAmerican’s San Juan assets and ended up with a lot of empty pipeline capacity, but there was the converted NGL line taking oil to market.

San Juan operators like Alexander’s company face a list of major challenges including regulatory, financial, technological and market demand issues. There is a new waste rule from the New Mexico Oil Conservation Division, and a second rule coming from the state Environmental Improvement Division based on improving ozone reduction attainment statewide. The latter promises to be a “considerable hurdle to overcome,” according to Alexander. “It’s going to have its biggest impact on small producers and low-producing wells,” he added.

Help may come in the form of technological advancements in new ways to not only better identify methane leaks, but also to accurately quantify them. “There are still too many unknown factors,” Alexander said. “And even with all the technology advances, you still have to go out physically and repair leaks and measure them.” While citing additions like smart pigs, micro-pressure measurements and certified natural gas technology, Alexander acknowledges that he still dreams of the day when “we are not venting any gas at all.”

In July, the Gas Technology Institute (GTI) hosted a webinar on “Minimizing Methane Emissions from Natural Gas Systems,” aimed at what it called the “frequent gap between bottom-up emission factor-based inventories and top-down measurements.” GTI’s Director for Gas Transition Solutions Erin Tullos, PhD, discussed the need to standardize a methane approach that incorporates measurements into emission inventories.

Eventually, this work will have relevance for the San Juan and the other western basins as operators continue to try to balance environmental and energy needs in a world still reawakening from the impacts of the pandemic.

Richard Nemec is P&GJ’s regular contributing writer based in Los Angeles. He can be reached at: rnemec@ca.rr.com.

Comments