April 2019, Vol. 246, No. 4

Features

Beyond the Tribal Effect: Steps to Successful Permitting on Native American Lands

By Rick Stevens and John Eisenhauer, Dawson & Associates

Within the energy industry, the sovereignty of tribal nations is a fact not simply worthy of consideration, but one that is essential to project planning. The benefits gained by establishing positive tribal nations relationships may result in significant time and cost savings.

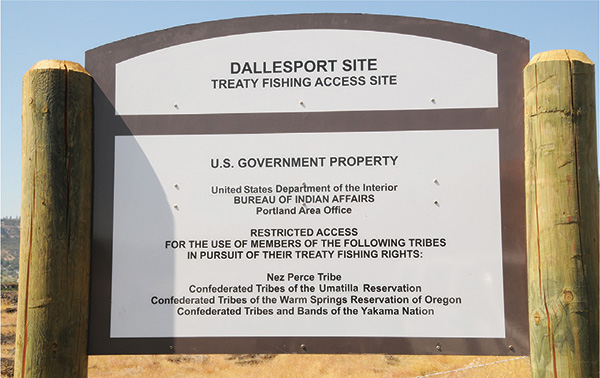

In 2017, the Department of Energy reported that American Indian land comprises only 2% of the U.S. land base, but some 30% of coal reserves west of the Mississippi River and 20% of known oil and gas reserves. Of specific concern to the pipeline industry, potential shipping routes for these commodities may at times cross tribal land or otherwise potentially impact tribal resources.

With so much at stake, permit applicants can’t afford to take shortcuts. This is especially true when considering the potential tribal implications of a proposed project. So, what are a few of the keys to a successful and sustainable permit? Our Corps of Engineers experience, combined with our more recent experiences in the private sector, inform five “best practices” for the energy industry:

‘Trust Relationship’

To address tribal interests successfully, applicants must first and foremost respect the relationship between the Corps of Engineers and Native American tribes. Indeed, go above and beyond what you might feel is necessary or prudent to demonstrate that respect in the early stages of project development. Remember, at any time, you may only be a “press release” away from what could ultimately grow into a public relations disaster.

Legally, if a project has more than a de minimis impact on tribal treaty rights, resources and lands, a tribe may have the final word on whether the project can proceed. In reality, based on our experience, tribes are hesitant to expose their reserved rights to litigation. Hence, if a tribe is willing to do so, it likely believes it has a solid record to support its claims and is therefore more likely to prevail.

Likewise, the Corps of Engineers has an extensive process for determining whether a project’s impact meets the de minimis threshold. Knowing that litigation can be costly and time consuming, early coordination may be the more preferred approach for all parties.

In addition, Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act requires federal agencies to consider a project’s impact on historic properties. It also requires U.S. government consultation with federally recognized tribes to protect cultural and archeological resources.

Corps of Engineers regulations based on these laws establish that federally recognized tribes have a preeminent right to be consulted on infrastructure projects, including pipelines, which potentially impact their lands, treaty rights, and protected resources. The Corps of Engineers, as part of the Department of the Army, has a “trust relationship” with tribes. That trust relationship means the Corps has a responsibility to represent and protect the rights of federally recognized Native American tribes.

Under Corps guidance updated in 2018, if a federally recognized tribe requests consultation, the Corps will grant it. Any company seeking Federal permits for infrastructure projects must assume that Native American consultation will be required and will be well served to meet and coordinate with Native American tribes at the outset.

Current Corps policy confirms the “unique relationship to federally recognized tribes, which is different than the relationship with state and local governments” [emphasis added]. This relationship is based on a combination of the U.S. Constitution, treaties, statutes, executive orders, administrative rules and regulations, and judicial decisions.”

Avoid Common Errors

Want to know the fastest way to stall a permit? Safeguard important details from the Corps in a permit application – especially required information related to project timing and deadline issues.

Illustrative of this pitfall, consider the recent experience of a large energy company, which was resolved to begin offshore construction operations near an area with potential tribal community implications. The project, designed to allow ship refueling, would help the company meet EPA emissions guidelines.

Typically, the energy company had established an internal timetable that carried significant penalties if unmet, but it never communicated to the Corps’ jurisdictional District either the deadline or the timing necessary to meet the company’s milestones. Regardless of its reasons, the company’s permit process plodded along more slowly than necessary, fueling its increasing concerns and frustrations.

When the company later shared its internal timeline constraints and priorities with the leader of the Corps’ District, its commander was able to facilitate the resolution of tribal concerns and ultimately help forge a compromise that moved the application forward. Ultimately, the project received approval.

Doing your best from the outset to provide a complete application, as defined by the Corps, can make a big difference.

Intertribal Disputes

Understanding intertribal disputes, with origins and histories that may date back hundreds of years, is critical, especially for interstate energy projects. Adding to potential frustration, these disputes may involve issues completely unrelated to the proposed project.

The Corps of Engineers is adept at mediating strategies impacted by intertribal disputes. Put your faith in them. Engage the district commander so he or she has the latitude to fashion compromise.

Case in point, the Crow Nation operates a coal mine in Montana. According to the official State of Montana website, “the vast coal deposits under the eastern portion of the [Crow Nation] reservation remained untapped.”

In contrast, the neighboring Northern Cheyenne tribe, who also have substantial untapped resources, have chosen not to mine their coal reserves, having affirmed in a March 2017 lawsuit against the federal government their belief that coal mining near their reservation would cause “significant environmental and socioeconomic harms to the tribe.” Here we have two tribes, each acting in accordance with an ideology seen to be in their own best interests.

Why do these differences in ideology matter? It’s clear that mined material or energy product has to get to market. That task can involve roadways, rail and other transport, often transiting neighboring tribal lands. To be sure, there’s no guarantee these neighboring tribes will share the same goals or perspectives. The objections of any one tribe has the potential to kill a project.

For permit applicants, any attempt to inject oneself into intertribal disputes is unwise. Despite best efforts and intentions, it’s difficult to overcome a perception of self-interest at the expense of the tribes. That said, Corps officials, with the right strategy and leeway in negotiation, can be effective third-party advocates.

Vital Communication

Once the permit process starts, proper communication with tribal leaders is vital. The prudent first step is to confirm whether the Corps of Engineers District overseeing the permit has a protocol for tribal consultation and coordination. Many Corps Districts have protocols in place; the Omaha District’s excellent “Missouri River Cultural Resources Agreement” is a fine example. Under the provisions of this agreement, the Corps “will take the lead on any proposed communication … with Tribal Government(s) or Tribal Historic Preservation Office(s).”

In 2010, the Corps’ Walla Walla District developed a similar approach necessitated by the multitude of tribal interests in the region. The Corps crafted a strategy to improve its tribal coordination in Idaho.

The district worked with nearly a dozen tribes to fashion a letter of agreement, subsequently signed by three tribes, that sets forth protocols involving notice and disclosure by the Corps. In return, the tribes committed to written replies within set time periods.

The effect achieved using a proven communications approach that is consistent, familiar, and clearly articulated is an overall reduction in project risk. The Corps is in a great position to identify and resolve issues before they become potential flash points.

If a tribe does not appear to be negotiating in good faith, applicants should consider having the Corps deliver permit-related requirements under the umbrella of consultation. It’s best not to do it yourself.

Corps vs. FERC

No discussion of federal permitting and tribal concerns would be complete without exploring the differing legal requirements – and therefore approaches – that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) often take with regard to tribal consultation.

Energy permits, especially for interstate gas pipeline projects and export terminals, typically require approval from both FERC and the Corps of Engineers. While the Corps is a cooperating agency with FERC, the Corps’ authority is separate and independent from FERC.

In practice, these agencies’ unique statutory authority and rules have the potential to create uncertainty for some applicants. This is no truer than when determining what constitutes proper consultation with affected Native American tribes.

There’s no question FERC takes its consultation responsibilities very seriously as evidenced by its “Policy Statement on Consultation with Indian tribes in Commission Proceedings” dated July 23, 2003. That document stipulates, “… the Commission will endeavor to work with the tribes on a government-to-government basis and will seek to address the effects of proposed projects on tribal rights and resources.” An important task for any permit applicant is to clearly understand the thresholds that define agency consultation for the agency with which they’ll be working.

The Corps of Engineers has a long history of requiring that Native American tribes be fully brought into the permit process. The Corps’ “Tribal Consultation Policy” published in 2012 directs, “Commands will ensure that all tribes with an interest in a particular activity…are contacted and their comments taken into consideration.”

In the Corps’ view, project sponsors almost invariably must obtain a tribal response as confirmation that consultation was made. For the energy industry, this often leads to confusion at what may appear to be excessive focus on Native American concerns.

Lest you think the Corps routinely provides unchecked veto authority to tribes, nothing could be further from the truth. In one case several years ago, the Corps’ Seattle District was immersed in a permit dispute between local tribes and a liquefied natural gas facility. In the opinion of the district leadership, tribal leaders were continually delaying responses and postponing meetings.

Ultimately, the district commander, who himself had been repeatedly rebuffed, delivered a firm message essentially asking the tribal leadership to join the effort in good faith negotiations or risk the process having to move forward without them. In the end, the application was approved.

Conclusion

In the midst of the 2016 DAPL controversy, Energy Transfer Partners Chairman and CEO, Kelcy Warren said the following in an official statement to his employees: “We – like all Americans – value and respect cultural diversity and the significant role that Native American culture plays in our nation’s history and its future and hope to be able to strengthen our relationship with the Native American communities…”

It’s reasonable to believe this core ideology is consistent across the energy industry. Likewise, a 2017 joint report issued by the Departments of Interior, Army and Justice entitled “Improving Tribal Consultation and Tribal Involvement in Federal Infrastructure Decisions” reinforced the position that tribes “are not universally opposed to infrastructure investments.”

The energy industry and our Nation’s tribes have much to offer one another. The more the energy industry understands and respects tribal culture while applying industry best practices that have consistently led to sustainable permit decisions, the higher the likelihood that their endeavors will be successful. P&GJ

Authors: Rick Stevens and John Eisenhauer are consultants at Washington-based environmental permitting firm Dawson & Associates. Retired Maj. Gen. Stevens served as deputy commander of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers from 2014 to 2017. Retired Col. Eisenhauer commanded the Corps of Engineers Portland District, 2011-2013.

Comments