August 2021, Vol. 248, No. 8

Features

Africa’s New Pipeline Projects – What to Expect During the Next Few Years

By Gordon Feller, Eurasia Correspondent

The World Bank released a special report on March 31 about the future of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), which found the region’s economic growth contracted by 2% in 2020. This was closer to the lower bound of the forecast it made in April 2020. But it also found that prospects for recovery and growth in SSA are strengthening.

This comes amid actions to contain new waves of the pandemic and speed up vaccine rollouts. The World Bank’s biannual economic analysis for the region is not the only expert analysis that is predicting this kind of near-term future.

SSA’s portfolio energy and utilities infrastructure projects total 870, which, taken together, are worth a combined $236 billion. These projects are at various pre-construction stages or under construction. These are the findings of a new research project conducted by Fitch Solutions, a New York-based company. Their analysts place the SSA’s pipeline as the second smallest among the world’s regions, ahead only of the Middle East and North Africa.

SSA’s oil and gas pipeline infrastructure project portfolio is dominated by Nigeria, which hosts 10 projects worth $7.2 billion. Much of the country’s oil and gas pipeline infrastructure has deteriorated as a result of conflict and vandalism. High operational risks and continued pipeline sabotage could incentivize international oil companies to further divest onshore Nigerian assets, posing a downside risk for the realization of the country’s project pipeline.

Mozambique hosts the most expensive oil and gas pipeline project in SSA’s project portfolio. The $5 billion GasNosu North-South Gas Pipeline ought to transport natural gas from Mozambique northern gas fields in Cabo Delgado province to Maputo and further to South Africa.

The outlook is dim for this project and its competitor, the African Renaissance Gas Pipeline, as operational risks in the Cabo Delgado province continue to delay construction of the liquefied natural gas (LNG) production projection and South Africa’s underdeveloped natural gas market limits demand for gas imports from Mozambique. In April, Total declared force majeure on its 13.2-mtpa Mozambique LNG project in Area 1, in northern Mozambique.

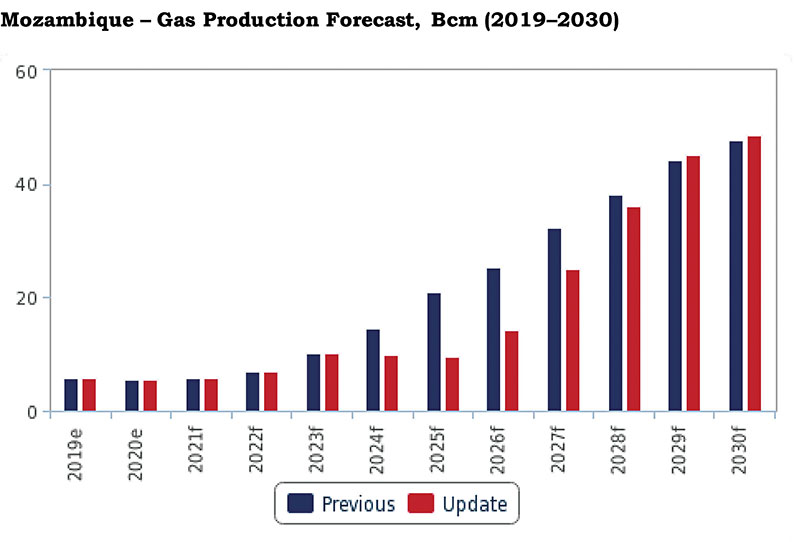

Total’s suspension means one can expect a significant delay to project start-up. Those who track this have revised Mozambique’s gas production forecast to include first gas from Mozambique LNG in 2026 – a two-year delay from previous expectations of 2024. Given the uncertainties regarding the resolution of the insurgency attacks, additional delays to this timeline are increasingly likely.

With the rapid spread of fighting throughout Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province, and with the resultant large-scale civilian population displacements, will this violence kill the multibillion-dollar LNG project situated there? Some experts think the terrorist attacks are likely to result in a wider military conflict.

These analysts are convinced that the project will fail, sooner or later, perhaps even during the next months. There is a third school of thought that argues that foreign governments, acting bilaterally and multilaterally, will attempt (and succeed, in some measure) to get the national government to do some of the right things, thereby reducing the local conflicts.

In light of the pandemic’s unprecedented shock, and rapidly shifting demand for gas around the world, can this Total project succeed in the long-term? One answer can be found in “Gas 2020,” a special report from the International Energy Agency (IEA; based in Paris), which analyzed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on global natural gas markets.

The study concluded that 2020 saw “the largest recorded demand shock in the history of global natural gas markets.”

It details how the COVID-19 pandemic hit an already declining gas demand, faced with historically mild temperatures over the first months of the year. Gas consumption is expected to fall by 4% in 2020, under the successive impacts of lower heating demand from the warm winter, the implementation of lockdown measures in almost all countries and territories to slow the spread of the virus, and a lower level of activity caused by the COVID-19-induced macroeconomic crisis.”

Natural gas markets are going through a strong supply and trade adjustment, resulting in what the IEA calls “historically low spot prices and high volatility.” They conclude that “natural gas demand is expected to progressively recover in 2021; however, the COVID-19 crisis will have longer-lasting impacts on natural gas markets as the main medium-term drivers are subject to high uncertainty.”

After a slowdown in annual growth in 2019, “natural gas consumption was negatively impacted in early 2020 by an exceptionally mild winter in the northern hemisphere.”

This was soon followed by the imposition of partial to complete lockdown measures in response to COVID-19 and an economic downturn in almost all countries and territories worldwide.

“As of early June, all major gas markets are experiencing a fall in demand or sluggish growth at best as is the case of the People’s Republic of China. Europe is the hardest hit market, with a 7% year-on-year decline so far in 2020,” the study said. “The global oversupply is pushing major natural gas spot indices to historic lows, while the oil and gas industry is cutting spending and postponing or canceling some investment decisions to make up for the severe shortfall in revenue.”

One key IEA conclusion is that LNG “is expected to remain the main driver behind global gas trade growth, but it faces the risk of prolonged overcapacity as the build-up in new export capacity from past investment decisions outpaces slower than expected demand growth.”

The U.S. federal government’s position is summarized in a key statement made by the U.S. State Department in the “2020 Investment Climate Statement for Mozambique,” which states “Mozambique stands on the cusp of transformative economic growth driven by the development of one the largest natural gas discoveries in the world. In the next five years, Mozambique expects to see nearly $60 billion in investment to develop its offshore natural gas reserves and an onshore facility that will convert the gas to liquefied natural gas (LNG) for export to global markets.”

However, the State Department went on to say that between the combination of the outbreak of COVID-19, an increasingly violent extremist movement in northern Mozambique, and the impact of the global downturn on Mozambique’s resource-dependent economy, the start of that transformation is likely to be delayed.

The U.S. government’s conclusions are not too dissimilar from the conclusions drawn by the independent researchers at Transparency International (TI), the highly respected international non-governmental organization (INGO).

In its “TI Corruption Perceptions Index, 2020,” the INGO ranked the country as 149th in a total of 180 countries. Since its launch in 1995, Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) has become the leading global indicator of public sector corruption. CPI offers an annual snapshot of the relative degree of corruption by ranking countries and territories from all over the globe.

TI’s “Global Corruption Barometer 2019” found that 49% of those surveyed thought corruption increased in the previous 12 months. The Global Corruption Barometer (GCB) also found that 35% of public service users paid a bribe in the previous 12 months. Since its debut in 2003, GCB has surveyed the experiences of everyday people confronting corruption around the world. Tens of thousands around the globe are asked about their views and experiences, making it the only worldwide public opinion survey on corruption.

A special TI report was published in December 2019: “Grand Corruption and the SDGs: The Visible Costs of Mozambique’s Hidden Debts Scandal.” It looked back to the start of the 2010s, when there “was real optimism that newly discovered resource wealth could help Mozambique overcome its acute development challenges.”

That optimism has now been completely shattered by the gross corruption displayed by all of the key actors: Mozambique’s government executives, both national and local; Mozambique’s local companies; foreign companies.

Here are five of the primary risks that this mega-project now faces:

Suppressed gas prices and the risk of stranded assets – Why LNG prices could be suppressed for at least another 15 years – and likely longer as the world moves permanently away from fossil fuels.

2. Security and human rights – The gas developments are believed to be one of the factors fueling tensions that led to the launch of the insurgency in October 2017. The war has so far resulted in well over 600 civilian deaths and contributed to the displacement of 211,485 people.

Corruption and governance risks – In 2013 and 2014, Mozambique’s security establishment took out $2 billion in hidden debt to buy a marine security package that they hoped would allow them to win multimillion-dollar contracts to protect the LNG projects. The debts bankrupted the country.

Russia and criticism of elections – Companies linked to oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin, dubbed “Putin’s chef,” helped deliver victory for the ruling Frelimo party in the 2019 election, as well as mercenaries to fight the insurgency in Cabo Delgado.

Other local financial, environmental and social risks – The Mozambique LNG project threatens local livelihoods, biodiversity and natural defenses against climate change in Cabo Delgado, while volatile commodity prices and poor governance means it may not deliver the promised revenues to either the state or the local population.

Jason Feer, global head of Business Intelligence at Poten & Partners, said the project represents a move away from how LNG liquefaction projects have been developed traditionally, while still retaining many of the elements that have been used in LNG projects.

In his view, it “resembles traditional LNG projects in that the developers pre-sold the majority of capacity to creditworthy off-takers under long-term contracts. The developers then were able to secure project finance loans based on these long-term commitments. The off-takers were mostly a mix of Asian and European utilities and international oil companies.”

However, as Feer looks at the project’s details, he sees a number of crucial differences: “Traditionally, most legacy LNG contracts with new projects were for at least 20 years and they were nearly always priced against crude oil prices, most frequently Dated Brent,” but also against crude baskets such as the Japan Crude Cocktail or Japan Customs Cleared crude price or similar baskets from Korea or Indonesia.

“First, contract lengths varied from 13 to 20 years, a much greater range than normally seen. More importantly, the pricing of these volumes varied widely, depending on the gas markets in regions where volumes would be exported,” Feer said.

Ning Lin, chief economist of the Center for Energy Economics at The University of Texas, has a different view. She points to the fact that Africa has a relatively small base of gas consumption, “but it has the second fastest growth rate around 3% in the next two decades, after Asia.” She argues that “the key driver of natural gas demand for Africa is electric generation.”

About 580 million people in sub-Saharan Africa lacked access to electricity in 2019, three-quarters of the global total.

“In the year 2020 with the pandemic, the number of people without access to electricity in sub-Saharan Africa is expected to rise according to World Bank,” she said. “Mozambique has the potential as a leader to contribute to the advancement of sub-Saharan Africa’s energy and economic growth.”

There are three LNG projects in Mozambique, two traditional liquefaction projects – Mozambique LNG by Total with 43 mtpa and Rovuma LNG by ExxonMobil with 15 mtpa, and one FLNG (floating LNG liquefaction) Coral South FLNG by ENI with 3.4 mtpa.

Lin feels in the short-term, 2024–2026, there are major expansions of LNG liquefaction coming online from North America, followed by Russia, Middle East, and Africa, with increments of 330 million tons in capacity (4.3 Bcf/d).

“So, Mozambique LNG has some competition at the beginning. Note in the chart, we do assume it takes up to at least 24 months for Mozambique LNG project to be online with full capacity,” she said.

In the long-term, the LNG cargo would be destined for the Asian market, although there’s fierce competition for the Northeast Asia market, which includes China, South Korea and Japan, against Russia, Qatar and Australia LNG cargos.

CNOOC signed a sales and purchase agreement (SPA) for 1.5 mtpa for 13 years, while one Japanese bank has loaned up to $536 million to support the Mitsui/JOGMEC partnership with Total to develop upstream gas field, feeding gas to the onshore LNG liquefaction plant.

“This does not necessarily imply the LNG destinations would be in China and Japan alone, but it indicates confidence and support from major LNG buyers as a valuable asset for global LNG trade.”

Significant challenges must be addressed for Mozambique to fully monetize the potential in its gas resource.

Comments