Applying Common Sense to Midstream Pressure Vessel Inspections

By W. MCBRIDE, XCEL Group, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma (U.S.)

(P&GJ) — The mechanical integrity (MI) landscape in midstream operations presents unique challenges that demand both technical expertise and practical application of industry standards. While regulatory frameworks such as the American Petroleum Institute (API) 510 and the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) Section VIII provide comprehensive guidance for pressure vessel inspections, successful implementation often requires understanding the nuanced interpretation of these codes, particularly when documentation is incomplete or missing. While maintaining recognized and generally accepted good engineering practices (RAGAGEP), a common-sense approach can be taken in many aspects of an MI program.

The documentation challenge

A significant issue facing midstream facilities involves pressure vessels operating without complete design documentation. When pressure vessels are manufactured, they receive what industry professionals refer to as a "birth certificate", formally known as the ASME Manufacturer's Data Report Form U-1A. This document contains comprehensive materials of construction data, design specifications and fabrication details essential for proper inspection and fitness-for-service evaluations.

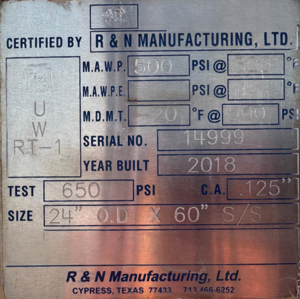

Older facilities frequently encounter situations where these critical documents have been lost, destroyed or were never properly maintained. Without the U-1A form, inspectors must rely on the vessel's data plate, which provides limited information typically restricted to operating pressure and temperature ratings. An even bigger issue within midstream is many vessels built around the 1940s through the 1980s lacking design plates and documents. Certain common-sense mitigations can be used by default to help these vessels stay in use, but their maximum operating pressures allowed are decreased significantly, minimizing their use.

Default material assumptions and their limitations

When design documentation is unavailable, API 510 requires defaulting to the lowest tensile strength carbon steel material known for pressure vessel construction: SA-283 Grade C. This conservative approach, while adhering to code requirements, often results in inspection failures that may be unnecessarily restrictive. Along with the default material specification of SA-283 Grade C, the vessel seam joint efficiency is also assumed to be 70% by default. The joint efficiency of the pressure vessel calculation is extremely important in gaining the proper minimum required thickness calculation of the vessel.

The fundamental issue lies in understanding the manufacturing process. Traditional pressure vessels are constructed from flat carbon steel plates that are heated, tempered, rolled and joined with a longitudinal seam weld. However, many vessels, particularly smaller units such as filters and compression equipment, are manufactured from seamless pipe stock rather than rolled plate. The longitudinal seam weld is either radiographed or not during manufacturing, and the more radiograph that is involved will allow for a lower minimum required thickness (FIG. 1).

The seamless vessel advantage

For vessels constructed from pipe rather than rolled plate, the absence of a longitudinal seam presents a significant advantage in material property assumptions. The weakest pipe material specification, SA-53 Grade B, possesses tensile strength equivalent to SA-106, which matches commonly specified materials for pressure piping systems. Crucially, these materials demonstrate substantially higher strength characteristics than the default SA-283 Grade C assumption.

Case study example

A midstream operator with over 30 facilities was experiencing systematic failures of compressor package vessels during routine inspections. All affected vessels lacked proper ASME code stamps and were being evaluated using SA-283 Grade C assumptions using a joint efficiency of 70% as stipulated by API-510, resulting in de-rated operating pressures that significantly limited compressor capacity and throughput.

Upon detailed examination, these vessels were identified as seamless construction manufactured from pipe stock. By applying SA-53 Grade B material properties, justified by the absence of longitudinal seams and using a joint efficiency of 85% as allowed per API-510, 95% of the previously failing vessels achieved compliance at their original design pressures. This approach was subsequently validated during an Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) National Emphasis Program (NEP) audit without question, resulting in substantial cost savings and restored operational capacity.

Joint efficiency considerations

The concept of joint efficiency represents another area where practical application of code requirements can yield significant benefits. Joint efficiency is determined based on the level of radiography is performed on the seams during the manufacturing process, and the minimum required thickness calculation is based on the joint efficiency of the longitudinal seam in rolled vessels. ASME Section VIII recognizes four levels of radiographic examination (RT-1 through RT-4), each corresponding to specific joint efficiency values:

- RT-1 and RT-2: 100% joint efficiency (full radiographic examination)

- RT-3: 85% joint efficiency (spot radiography)

- RT-4: 70% joint efficiency (no radiography)

Without design documentation, conservative practice defaults to 70% joint efficiency. However, for seamless vessels constructed from pipe, the absence of longitudinal seams permits application of 85% joint efficiency as a minimum baseline, significantly improving calculated allowable stresses.

Data plate information utilization

Vessel data plates frequently contain radiographic examination indicators that can inform joint efficiency determinations. Historical marking systems evolved from "XR" (full X-ray), "PXR" (partial X-ray) and no marking, to "RT", "PRT" and no marking, and finally to the current RT-1 through RT-4 system implemented in the early 1990s.

Rather than automatically defaulting to the most conservative assumptions, careful examination of data plate markings can provide justification for higher joint efficiency values, thereby improving the likelihood of successful fitness-for-service evaluations. The key indicator will always be the minimum required thickness calculation. For example, if the plate is marked “PRT”, a 70% joint efficiency may accidentally be used, and the design would indicate a higher minimum required thickness than the vessel’s nominal thickness. However, if you interpret “PRT” as “partial radiography testing” and apply an 85% joint efficiency in your calculation, the resulting minimum required thickness will more closely match the vessel’s nominal thickness or lower (FIG. 2).

Risk management and industry practice

The MI community often demonstrates excessive conservatism when interpreting code requirements, driven by concerns about safety, regulatory compliance and potential audit findings. While prudent risk management remains essential, this approach can result in unnecessary equipment replacements, operational restrictions and associated costs.

The key lies in understanding that engineering codes are interpretive documents designed to accommodate various scenarios through sound engineering judgment. When supported by logical technical reasoning and documented justification, practical applications of code provisions can achieve both safety objectives and operational requirements.

Implementation recommendations

Successful application of these principles requires:

-

Thorough documentation: Maintain detailed records of all inspection findings, technical justifications and decision-making rationale. A U1-A specifically is not always the only document needed as most of the design variables can be found on construction drawings, engineered data sheets and stamping.

-

Cross-functional collaboration: Engage owner-user engineers, inspection personnel and operations teams in evaluation discussions while determining the safest approach to support equipment passes.

-

Regulatory awareness: Ensure all approaches align with applicable regulatory requirements and industry best practices (RAGAGEP).

-

Continuous validation: Regularly review and update assumptions based on operational experience and industry developments.

Takeaway

Effective MI programs balance regulatory compliance with practical operational requirements. By applying sound engineering judgment to code interpretation, particularly regarding material assumptions and joint efficiency determinations, midstream operators can achieve significant cost savings while maintaining appropriate safety margins.

The pressure vessel inspection challenges discussed represent common industry scenarios where technical expertise, combined with thorough understanding of applicable codes and standards, can prevent unnecessary operational disruptions. Success requires moving beyond default conservative assumptions to embrace technically justified approaches that serve both safety and business objectives.

As the midstream industry continues evolving, MI programs must adapt to leverage available technical knowledge while maintaining the highest standards of operational safety. The principles outlined in this article provide a framework for achieving these dual objectives through informed, practical application of established industry codes and standards.

About the author

WILLIAM MCBRIDE is the General Manager for MI at XCEL. He has spent approximately 20 yrs in the midstream business with many roles in operations, engineering and project management. Of the 20 yrs, 15 yrs have been dedicated to the element of MI under OSHA’s Process Safety Management Program 1910.119. As a professional that has worked on both sides of the business (owner/user and contractor), McBride has experienced a multitude of situations within the process safety management MI business. McBride also sits on several midstream committees, such as the GPA Midstream integrity committee, to stay ahead of recommended practices and industry changes.