May 2014, Vol. 241, No. 5

Features

How Louisiana Satisfies Growing Southern Gas Market Demand

For more than a half century the state of Louisiana has been one of North America’s largest natural gas producers and home to a pipeline grid that is the crossroads of the industry.

Through that grid, Louisiana has been a primary gas supplier to markets across the continent as traders tapped countless gas production fields and pipeline interconnections, and managed their business with a vast complex of natural gas storage facilities that dot the state. Like much of the natural gas industry, however, Louisiana is undergoing material changes that may now turn it into one of North America’s fastest growing demand centers.

This reversal of fortune, from big supplier to big consumer, along other trends, could significantly affect the supply-demand balance in the state. Always a source of supply abundance, a tighter market looms as Louisiana gas demand accelerates in the face of declining access to the state’s conventional supply sources and uncertainties about the access to new supplies that will need to come from outside of the state.

Surging Louisiana Gas Demand

Gas demand growth in Louisiana is expected to come from a diverse collection of end users, geographic markets and load profiles. The principal drivers of growth will likely be LNG exports, gas-fired power generation in the Southeast and in-state petrochemical and industrial demand. The common thread is that overall consumption will increase substantially over the coming years.

LNG exports are likely to be the largest growth source as North American shale resources are attracting buyers from across the globe. Although project sponsors are backing LNG proposals on the East, West and Gulf coasts of the United States and Canada, Louisiana projects appear to have captured an early market share. There are several reasons for this, including the presence of good brownfield sites, pipeline capacity and shipping considerations.

One of the biggest factors, however, is the expectation of plentiful gas supplies in Louisiana. As much as 4-6 Bcf/d of LNG export capacity may be built along the Louisiana coast line in the next five years, with potential for an additional 3-4 Bcf/d by early in the next decade. Given this demand, international buyers are already developing supply procurement and investment strategies.

An interesting development is the mixed industry view on whether LNG exports will uniformly operate as baseload markets, or gas-fired generation will consistently dispatch. With the rapid ramp-up of new production capacity in the United States and Australia, global LNG markets may have surplus supplies during the non-winter months. Given U.S. storage capacity and flexible markets, the nation may for a time assume the role of global market swing supplier.

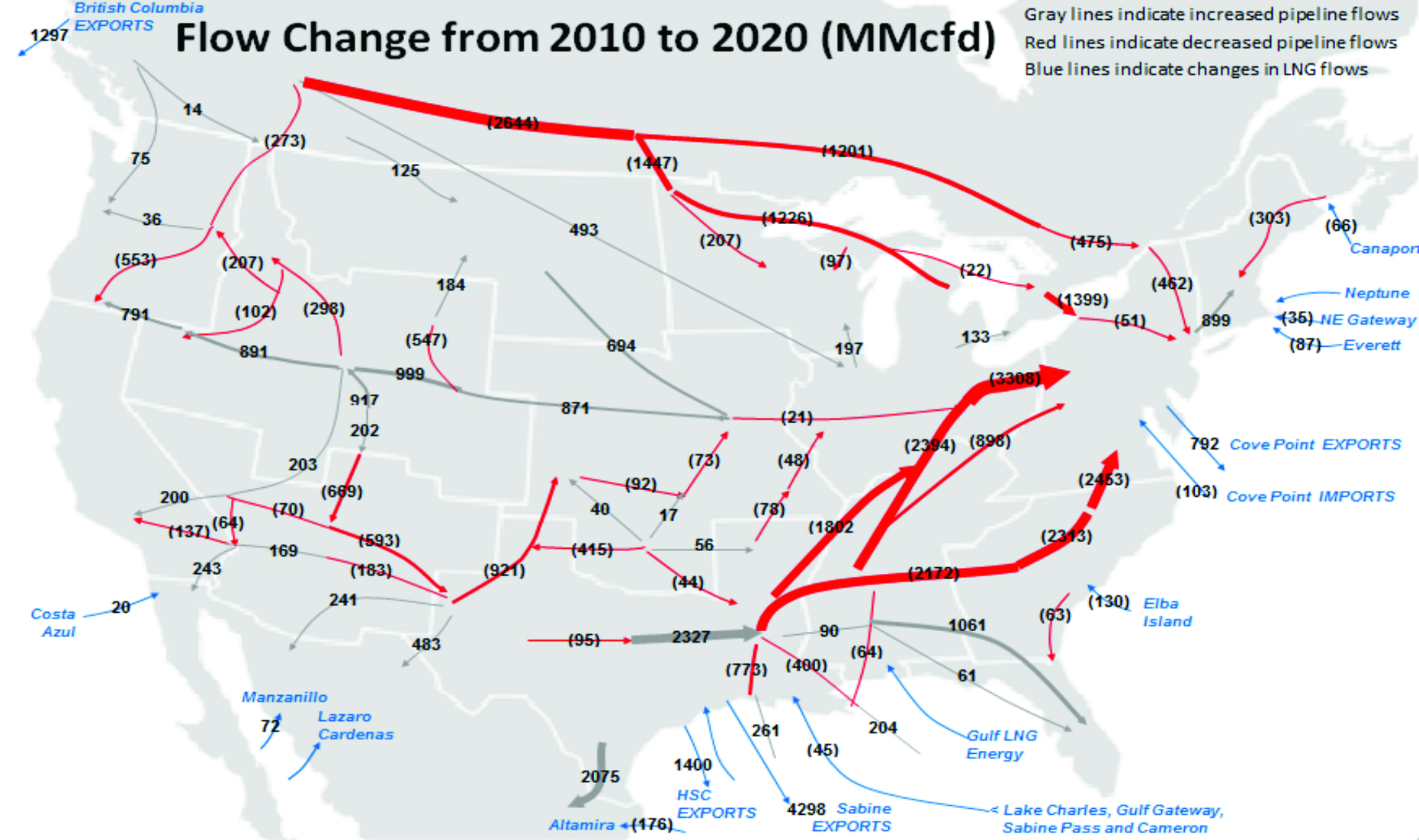

Over the coming decade the Southeast, led by gas-fired power generation, is poised to be one of North America’s fastest growing markets (See map). Incremental Southeast gas demand is projected to grow by more than 1 Tcf/yr by 2025, which is equivalent to more than 3 Bcf/d. Only the aggregated West South Central region (which includes Louisiana, Texas, Oklahoma and Arkansas) comes close to matching that rate of growth.

Regional Consumption

Southeast gas consumption growth can be aggregated into Louisiana demand analyses because the majority of new supplies flowing on pipelines serving the region will likely be sourced at pipeline interconnections in Louisiana. An important consideration for Southeast fuel buyers will be determining the best way to manage the seasonal and intermittent nature of that gas-fired generation demand, as these types of loads place a premium on flexible infrastructure to help match supply and demand.

It will also be interesting to see whether fuel buyers manage the competition for dwindling southern Louisiana production by reorienting their portfolios to northern Louisiana interconnections, where the majority of new shale gas supplies will first enter the state.

Widening U.S. oil and gas price spreads and a surge in natural gas liquids production have spurred a boom in planned new petrochemical plant construction in Louisiana and other parts of the Gulf Coast. These plants will require reliable and economic natural gas supplies to support the contemplated levels of investment.

All together, these three major gas demand sources could nearly double Louisiana’s annual gas demand as early as 2020 with a cumulative daily load growth that approaches nearly 10 Bcf/d by 2025.

Changing Of The Guard

Louisiana’s gas supplies have historically come from three conventional sources: Texas, the Gulf of Mexico, and onshore Louisiana. When combined with a well-developed pipeline and storage grid, the result was a Louisiana gas market that offered liquidity and supply security for buyers and sellers. This supply infrastructure is a primary attraction for new large gas users, but Louisiana’s access to gas reserves and production has decreased materially in recent years.

None of these conventional sources have grown in recent years, and as noted, offshore Louisiana production has decreased significantly. Absent new supply sources, the new gas users discussed above will compete with existing buyers for a dwindling supply base.

Historically, a large percentage of gas flowing through Louisiana originated in Texas, but those flows have decreased sharply and many pipelines exiting Texas into Louisiana are experiencing unprecedented low load factors. The emergence of Marcellus supply alternatives closer to the market is a major culprit. Rising Texas demand is another. Notwithstanding the rapid build in Eagle Ford production, going forward, pipeline exports to Mexico, LNG exports and rising industrial demand, may all serve to keep Texas production in-state, and compel Louisiana buyers to look for other alternatives.

Tennessee Gas Pipeline: 2007-2013 – The offshore Gulf of Mexico has been a primary source of Louisiana supply since the first offshore platforms started producing in the early 1950s. Production in the state and federal waters has since gone through numerous cycles, but at its peak offshore production once topped 11 Bcf/d. Year-end estimates for 2012 now show offshore gas production has fallen by more than 70% to roughly 3.3 Bcf/d with no near-term signs of a trend reversal.

Louisiana Gas Production: 2000-2020 – Louisiana’s prospect for rising demand against a tightening supply outlook is a high-class problem, and fortunately there are potential gas supply solutions. Going forward, unconventional supplies from the Marcellus formations in the Appalachian Basin, the Haynesville formations on the Texas/Louisiana border may become the primary gas sources for Louisiana’s growing demand. [1]

ICF expects the Marcellus to capture a significant share of Louisiana’s early growing demand growth, in large part owing to its generally superior economics when compared to other North American shale and non-conventional gas plays. Year-end 2013 statistics show Marcellus producers again outpaced expectations and pushed total production in the basin to roughly 13 Bcf/d. That success has already spawned several pipeline firm transportation contracts southward to Louisiana with both producers and fuel buyers. More firm contracts to Louisiana delivery points are likely.

The strides made in the Marcellus have overshadowed Haynesville in recent years, but the Haynesville is positioned to make significant contributions to North American gas production. As seen in the graph above, ICF’s “Natural Gas Strategic Outlook” projects that Haynesville production will rebound from recent declines to capture nearly 6 Bcf/d of increased U.S. market demand through 2025.

Common Thread

The overall outlook for Louisiana supply adequacy is positive, but much of the new Marcellus and Haynesville gas reserves are found outside of the state and this raises uncertainties.

The sequential emergence of cost-competitive North American shale supplies followed by increasing Louisiana gas demand is still in the early stage development. It is natural to expect uncertainties, in particular those relating to whether, how and when gas supplies and demand will ultimately be linked together. Some of the more prominent are noted in this section.

The Marcellus and Haynesville plays show tremendous promise, but Louisiana buyers know they are not the only region looking to these basins for future supplies. New England, the Northeast, eastern Canada and Upper Midwest gas users all have designs on transporting increased quantities of Marcellus production into their region as demand grows and other supply sources wane. If southern LNG exporters, Gulf Coast industrial plant operators, and Southeast power generators all view Louisiana as the natural origination point for significant shares of their future gas, they will need to make fuel procurement arrangements that allow them to deal with having so many markets tapping the same supply sources.

While Marcellus and Haynesville shale producers have generally good access to interstate pipelines that could deliver gas to Louisiana, new investments will be needed to reverse, expand or construct new segments on those pipeline systems. Since gas pipeline operators do not or cannot build speculative projects, incremental firm contracts will be required of shippers who will make long-term commitments to paying fixed charges for new capacity. Those transportation fees can be costly. Ultimately, the success of connecting Louisiana to any gas play will be a question of whether producers bear the costs by integrating downstream into the market, or buyers do the same and integrate upstream.

Timing For New Infrastructure

The Marcellus provides a good illustration of timing uncertainty because delivering that gas to Louisiana poses operational and regulatory challenges. To date, interstate pipelines have been able to provide north-to-south transportation through backhaul displacement services, which basically divert northbound flows from Louisiana to local delivery points and redirect Marcellus gas receipts to delivery points scheduled by south-to-north shippers.

There is a limit to backhaul services, however, because they are contingent on northbound flows of gas. When a pipeline becomes fully unloaded, it will then need to reverse the pipeline flows operationally. As seen, the large red arrows (map) indicate reductions in flows, much of which may be caused by increased backhaul displacements. The implication is that the day for needing to physically reverse flows southward is rapidly approaching for many pipeline systems.

Assuming a clear business model emerges on who will subscribe to pipeline capacity, in most cases, reversing the flow of a pipeline is not too complex. But new capacity investments can take time as pipeline companies host open seasons, negotiate contracts, design facilities and obtain regulatory approvals.

Reversing flows on pipelines from the Marcellus prompts numerous commercial questions. Several pipelines have reportedly sought and received maximum firm transportation (FT) rate contracts for backhaul/reverse flow services. This makes sense in the current basis environment in which Marcellus pricing points have traded at discounts to the Louisiana points. But in the longer term ICF projects a narrowing Marcellus discount or even at parity with Louisiana points. The important point is that it will be interesting to see how portfolio managers reconcile committing to long-term firm, fixed-price transportation contracts that may flow against flat or even negative basis differentials.

Implications For Producers

Louisiana’s long-term supply adequacy will depend in large part on two things: 1) market dynamics must attract supplies to the state from basins outside the state, and 2) Louisiana’s gas infrastructure must be able to match the ebb and flow of shifting supply sources with a diverse set of demand profiles and locations. The supply uncertainties described above are not likely to be deal breakers for large gas consumers or the state’s gas industry in general.

More likely, uncertainties will be underlying causes for delay in expanded supply sources and mismatches in supply access with the ramping of demand. The associated consequences may signal opportunities or suboptimal decisions by stakeholders. Some of the most prominent implications are:

Gas Price and Basis Behavior – Changes in Louisiana’s supply-demand equilibrium will matter for a host of reasons, the most obvious being the impact on gas prices. Growing gas markets that lack adequate supply or infrastructure, or both, typically signal these deficiencies through increasing price volatility and decreasing transaction liquidity. Such conditions in turn can lead to reduced trading volumes and price transparency at some market locations. Neither behavior is particularly conducive to growing gas demand.

Pipeline Rate Cases – For pipelines exiting the Marcellus (and Haynesville) Shale, Louisiana’s growing gas demand represents an opportunity to stem throughput losses experienced in recent years and bring new firm shippers onto the grid. These new loads will not go unnoticed by utility and other Northeast and Midwest shippers who continue to hold (and pay reservation charges for) long-haul contracts. In one way or another, these shippers will likely want to share in the successes of a new set of Marcellus-to-Louisiana shipper contracts and revenues. Expect a series of rate cases that could redefine the way pipelines approach cost-of-service allocation and rate design.

Increased Storage Utilization – Gas storage values across North America have taken a beating in recent years as gas supplies proliferate and markets lag, and Louisiana storage has been no exception. But gas storage has always been a primary tool for dealing with supply uncertainty, and the salt domes and reservoirs that dot the Gulf Coast offer a solution against supply disruptions, pipeline delays and the varied load profiles that Southeast power generation and global LNG markets may pose. Instead of the financial arbitrage opportunities, gas storage values going forward are likely to be driven by operational capabilities and location.

North Louisiana Hub Development – Henry Hub, and southern Louisiana in general, has been the epicenter of gas trading since the 1990s and implementation of FERC Order 636. The region has more reported gas price points than any other in North America. But market dynamics in Louisiana going forward are favorable to increased trading in northern Louisiana, and thus the need for more developed hub services.

Conclusion

The supply and demand elements for a robust Louisiana gas market are in place, but the gas industry faces some important commercial and regulatory decisions on how to link North America’s growing gas production with emerging demand centers. For Louisiana, this will involve new approaches to operating old pipelines, infrastructure investments in pipelines and storage to optimize new demand profiles, and an expanded geographic perspective on where gas trading will take place. All in all, the future is promising and will be exciting to watch as it unfolds.

[1] The Haynesville reference here includes production in the proximate Bossier Sands, while the Marcellus reference here includes potential production in adjacent Utica Shale.

Authors: Greg Hopper is vice president of ICF International and regional director of the company’s Houston office. He holds primary responsibility for client management and development of advisory services across Gulf Coast and Midcontinent energy markets.

Kevin Greene is an analyst at ICF International in the Energy Advisory and Solutions group. Based in the Houston office, Greene supports the development and delivery of commercial oil and gas industry services to clients across the energy value chain.

Comments